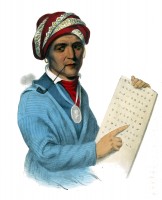

Liberty today sits on land that was once part of the Cherokee Indians’ hunting ground. The Otarre, or Lower Hill Cherokees, had several thriving villages along the riverbanks in the area; perhaps the most notable example being the village of Keowee, located near the modern day Oconee and Pickens County line. Cherokee tribesmen, who often survived by growing crops, and tended to live in small villages, were in many ways more domesticated than other Native American tribes. The Cherokee also hunted game, believing that the foothills were a sacred hunting ground for deer, buffalo, and other large animals.[6]

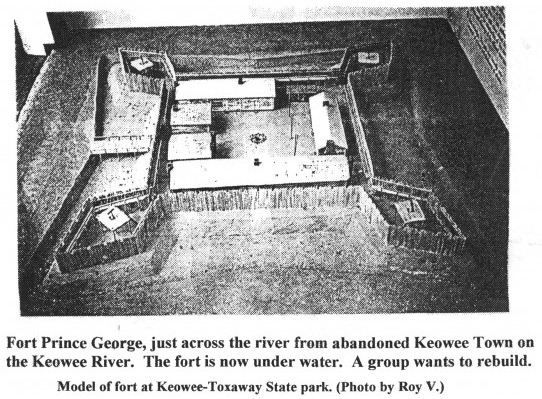

Tradition holds that Hernando DeSoto and his group of Spanish explorers were the first Europeans to travel through the area around year 1540.[7] The first Englishmen to venture into the area were traders who often traveled up from Charles Town and Savannah to exchange their guns, horses, cloth, and liquor with the Cherokee for animal skin and fur.[8] In 1753, British colonists built Fort Prince George, the first white settlement in Pickens County.[9]During the American Revolution the Cherokee chose to support the loyalists. South Carolinian patriots, angered at the Cherokee for supporting the Redcoats, forced them to cede much of their territory with the Treaty of DeWitt’s Corner in 1777.[10] American settlers did not start moving into the area in large numbers until the mid-1780’s.

Much of the history of the Liberty area in the late 18th century is unknown. By 1800, Liberty—then called Liberty Spring—was included in the newly formed Pendleton District, which included most of modern-day Anderson, Oconee, and Pickens Counties. During the Antebellum period, most people living in Liberty Spring were subsistence farmers: farmers who grew only what they needed to survive. Few in the area could afford to own slaves like the wealthier planters in the Low-country, and almost every farmer was forced to work the land himself. Even for those who wished to trade with other towns, the poor roads made the effort to transport goods cost more than those goods were often worth. Outside of church, local residents had few opportunities to socialize with each other. By 1826, the Pendleton District had split up into Pickens and Anderson Districts, with Liberty becoming part of the new Pickens District, which included both Pickens and Oconee Counties.

In 1860, a group of Pickens County delegates went to Columbia, where they—along with every other South Carolina delegate—voted unanimously in favor of South Carolina’s secession from the Union.[11] Though it is generally accepted that the first shot of the Civil War occurred when the Union ship Star of the West was fired upon from state troops at Morris Island on January 9, 1861, an old legend claims that a local resident named William Mauldin fired upon the Union ship from Fort Moultrie a few hours earlier, making his the first shot of the War.[12] Either way, what is known is that men from almost every family in the area enlisted to fight for the Confederate cause. Many families lost two, three, or more sons to the war effort. Several companies of infantry and cavalry were formed in Pickens District before being dispatched to serve under one of the state regiments. The men who either refused to enlist or deserted in battle were often thought upon with scorn by their neighbors for the rest of their lives, and even their descendants were often ostracized for years afterwards. The women who stayed behind willingly suffered through the whole war by doing without foods and supplies that were needed in the war effort.[13]

After the war, Pickens District, like the rest of the South, was placed under martial law by Union troops.[14] With little choice in the matter, South Carolina was readmitted to the Union in 1868. Not long afterwards, Pickens District was separated into the modern day Pickens and Oconee Counties. Between 1865 and 1877, southerners had little control over their government. Gangs of Union troops sacked and looted many farms in Pickens County during this period, known as Reconstruction, and the county and state governments were largely controlled by Northerners who moved South after the war.[15] Reconstruction officially ended in South Carolina around year 1877, not long after former Confederate General Wade Hampton III was elected governor under the Democratic ticket.[16]

Liberty’s official recognition as a town came soon after the Charlotte-Atlanta Airline Railway was completed in the early 1870s.[17] Former Confederate General William Easley, a lawyer working for the railroad company, negotiated to have the tracks laid through the southern part of Pickens County. It is along these tracks that the towns of Liberty, Easley, and Central all grew. By 1873, Liberty Station was built north of Liberty Spring after Mrs. Catherine Templeton deeded her land to the railroad company. John T. Boggs set up the new Liberty Post Office that same year, and was named the town’s first postmaster.[18] Liberty was formally chartered on March 2, 1876, with the future town center being located on the former lands of Mrs. Templeton.

In 1877, James Avenger was appointed the town’s first marshal. The marshall, a forerunner to today’s chief of police, was satirized in a Pickens Sentinel article that claimed, “there was nothing for him to do, except to look after the cows that go astray.”[19] The town’s first mayor W.E. Holcombe, a lawyer and former state senator, was elected in 1876.[20] He, like every succeeding mayor until the early 20th century, conducted most municipal business in his own home. Several schools were already in operation by this time, with most being privately funded, and sponsored either by the community or by the local churches. The Liberty First Baptist Church had existed prior to the city’s founding, being located at the old Liberty Spring site.[21] Reports indicate the Church had a congregation as early as year 1802, when they met at an old log house north of the present-day town. The Liberty Presbyterian Church was built in 1883 at its present site; formerly the church’s members had worshiped at Mt. Carmel Church in the country.[22]

Liberty’s next change came in 1901, when Mr. Jeptha P. Smith organized and started the first cotton mill, which he named the Liberty Mill. The original mill contained a card room and operating spinning frame. Eighteen houses and two overseer houses were built as a mill village to house the plant’s workers and their families. The second cotton mill was built by Mr. Lang Clayton of Norris in 1905. Built in a part of town often referred to as Rabbit Town, the plant was originally named the Calumet Mill, and later renamed the Maplecroft Mill. By 1920, both mills had come under the control of

Woodside Mills. The first mill became known as Woodside Liberty Plant #1 (commonly called the Big Mill), and the second as Woodside Liberty Plant #2 (commonly called the Little Mill). Woodside Mills operated the plants until 1956, when the company was purchased by Dan River Mills of Virginia. At their height in the 1970s, the mills employed over one thousand workers and housed over one thousand looms.[23] In the 1970s, the Woodside Liberty Mills were the world’s largest producers of oxford fabric, a popular fabric of the era. The mills were again purchased in the early 1980s by Greenwood Mills, which maintained control of the mills until local textile industry declined in the 1990s due largely to foreign competition. In 2013 the little mill was demolished. The Big Mill is currently being stripped for demolition.

The growth of cotton mills in the area brought about a major shift in the way people lived. Many migrated away from farmlands to the mill villages, and went from growing food to survive to earning hourly wages in the mills. Though farming was a hard life, early mill life was grueling in its own right; mill workers—condescendingly referred to as lintheads—often worked twelve or more hours a day in unventilated rooms.[24] Nevertheless, most workers believed that they were fortunate just to have such work, and willingly worked in the same mills all their lives. In many mill village families, both the husband and wife worked in the same mill.

Outside of the mills, several other major changes also happened during this long time period. Electricity came to Liberty in 1910, when Mr. J. Warren Smith, a salesman, installed two gasoline generators downtown to operate the first street lights and the lights of several shops. By 1928, demand had increased to the point that Mr. Smith decided to sell his assets to Duke Power, which established a small office downtown.[25] The Liberty Fire Department was first established in 1925, with J. Warren Smith—the same man who brought electricity to Liberty—being named as the first fire chief. The Fire Department moved into its present building in 1974.[26] The first town library originated in 1947 as a small room located in the same building as City Hall. The Sarlin Community Library, the one in current use, was built at its present location in 1966.[27] Liberty’s police department was finally organized in the 1920s, when the city employed a chief of police and two policemen. The first telephone service came to Liberty in 1902, when Southern Bell installed a telephone switchboard in the same building as the post office. The first water plant for the town was built in 1918 on Black Snake Road. This plant initially supplied water to around one hundred homes. This plant was phased out by 1956 after a newer waterworks sight was built on Eighteen Mile Creek.[28]

The former Mohawk Carpet plant is currently occupied by Southern Vinyl Windows & Doors, a major employer in the area.

References:

6. McFall, Pearl. It Happened in Pickens County. Pickens, SC: The Sentinel Press, 1959. 8-11.

7. McFall, Pearl. “It Happened in Pickens County,” 7.

8. McFall, Pearl. “It Happened in Pickens County,” 15.

9. McFall, Pearl. “It Happened in Pickens County,” 21.

10. Woodson, Julia. Liberty, South Carolina: 1876-1976. Greenville, SC: A Press, 1992. 1.

11. McFall, Pearl. “It Happened in Pickens County,” 70.

12. McFall, Pearl. “It Happened in Pickens County,” 73.

13. McFall, Pearl. “It Happened in Pickens County,” 75.

14. McFall, Pearl. “It Happened in Pickens County,” 81.

15. McFall, Pearl. “It Happened in Pickens County,” 82.

16. McFall, Pearl. “It Happened in Pickens County,” 104.

17. Woodson, Julia. “Liberty.” 2

18. Woodson, Julia. “Liberty.” 3

19. Woodson, Julia. “Liberty.” 95

20. Woodson, Julia. “Liberty.” 93

21. Woodson, Julia. “Liberty.” 19

22. Woodson, Julia. “Liberty.” 22

23. Woodson, Julia. “Liberty.” 67-68.

24. Browning, Wilt. Linthead. Asheboro, NC: Down Home Press, 1991. A1.

25. Woodson, Julia. “Liberty.” 90-91.

26. Woodson, Julia. “Liberty.” 91.

27. Woodson, Julia. “Liberty.” 92.

28. Woodson, Julia. “Liberty.” 95-97.